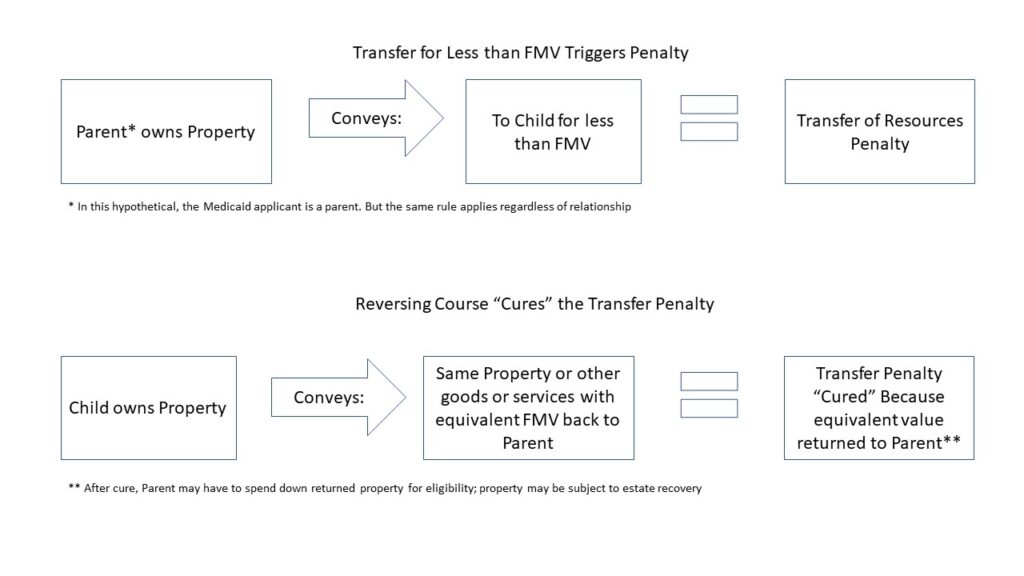

If resources were given away or sold for less than fair market value during the look back period, then Medicaid will impose a transfer of resources penalty. This is sometimes called a gift penalty. There is a significant amount of misinformation in the community regarding the transfer penalty.

One myth is that you cannot sell your home or other resources. You can always do anything that’s legal with your stuff. But there may be consequences for your actions. One possible consequence is the imposition of a transfer penalty.

One of the hallmarks of property ownership is the right to possess or dispose of property in any legal manner, consistent with the owner’s rights. Thus, if you own a home, the Medicaid rules do not prohibit you from possessing it, selling it or giving it away. To help you understand what we mean by “consequences,” it is helpful to think of Medicaid as the owner of its funds. Like you, Medicaid can possess or dispose of its funds. If you want medicaid to help you, then you must convince Medicaid to do so. That means following Medicaid’s rules. Giving your stuff away, or selling it for less than fair market value during the lookback period violates Medicaid’s rules.

The penalty provisions relating to asset transfers are found at 42 U.S.C. § 1396p(c)(1). The complete text of subsection (c)(1)(A) is as follows:

In order to meet the requirements of this subsection for purposes of section 1396a(a)(18) of this title, the State plan must provide that if an institutionalized individual or the spouse of such an individual (or, at the option of a State, a noninstitutionalized individual or the spouse of such an individual) disposes of assets for less than fair market value on or after the look-back date specified in subparagraph (B)(i), the individual is ineligible for medical assistance for services described in subparagraph (C)(i) (or, in the case of a noninstitutionalized individual, for the services described in subparagraph (C)(ii)) during the period beginning on the date specified in subparagraph (D) and equal to the number of months specified in subparagraph (E).

The elements of (c)(1)(A) are broken down and discussed below. However, it is critical to remember that these elements must be put back together and read as a whole to determine whether a penalty is applied.

1. Individual or spouse

Subsection (c)(1) of 42 U.S.C. § 1396p makes the asset transfer provisions applicable to an institutionalized individual and the individual’s spouse. At their option, States may also include noninstitutionalized individuals.

42 U.S.C. § 1396p(h)(3) defines the term “institutionalized individual” as an individual who is an inpatient in a nursing facility, who is an inpatient in a medical institution and with respect to whom payment is made based on a level of care provided in a nursing facility, or who is described in section 1396a(a)(10)(A)(ii)(VI) of this title. HCFA 64, § 3258.1(A)(4) expands the definition of institutionalized individual to include an individual who is “A home and community-based services recipient described in §1902(a)(10)(A)(ii)(VI) of the Act. For purposes of this section, a medical institution includes an intermediate care facility for the mentally retarded (ICF/MR). (See 42 CFR 435.1009.)”

Subsection (h) (4) defines the term “noninstitutionalized individual” to mean an individual receiving any of the services specified in subsection (c)(1)(C)(ii) of this section.

The spouse of an institutionalized spouse is defined as a “community spouse.” 42 U.S.C. § 1396r-5(h)(2).

As made clear in the next section, the actions of others who act on behalf of the applicant or the applicant’s spouse may be attributed to the applicant and spouse.

2. Disposes of

The phrase “disposes of” is not defined, but the second half of the definition of “assets” at Subsection (h)(1) makes it clear that any action separating the applicant from the asset is potentially suspect. The remaining language is as follows: “is entitled to but does not receive because of action— (A) by the individual or such individual’s spouse, (B) by a person, including a court or administrative body, with legal authority to act in place of or on behalf of the individual or such individual’s spouse, or (C) by any person, including any court or administrative body, acting at the direction or upon the request of the individual or such individual’s spouse.” The Georgia ABD Manual uses the phrase “gives away or sells assets for less than current market value.” POMS § SI 01150.001 indicates that a transfer takes place when “the individual no longer owns the property.” If the individual makes an alleged transfer that is not legally binding, then it is ineffective; no penalty applies because the individual still owns the asset. See POMS § SI 01150.001(B)(1).

“Disposes of” should have meaning consistent with the transfer of ownership or control under State law. Thus, a gift must be complete. For land, title must be transferred. In the case of Medders, a disclaimer must have been delivered. The following are examples of transactions which would result in a valid transfer if they are properly handled:

• Sale of property;

• Trade or exchange of one property for another;

• Spend-down of cash;

• Giving away cash;

• Transferring any financial instrument (e.g., stocks, bonds);

• Giving away property (including adding another person’s name as an owner of the property).

In addition, section 3257(b)(3) of HCFA 64 indicates that a transfer has occurred when an individual is entitled to receive assets, but not receive them because of any action of the individual. In that regard, HCFA 64 provides the following guidance:

The following are examples of actions which would cause income or resources not to be received:

• Irrevocably waiving pension income;

• Waiving the right to receive an inheritance;

• Not accepting or accessing injury settlements;

• Tort settlements which are diverted by the defendant into a trust or similar device to be held for the benefit of an individual who is a plaintiff; and

• Refusal to take legal action to obtain a court ordered payment that is not being paid, such as child support or alimony.

However, failure to cause assets to be received does not entail a transfer of assets for less than fair market value in all instances. For example, the individual may not be able to afford to take the necessary action to obtain the assets. Or, the cost of obtaining the assets may be greater than the assets are worth, thus effectively rendering the assets worthless to the individual. Examine the specific circumstances of each case before making a decision whether an uncompensated asset transfer occurred. (Emphasis added).

Loss of control can, in some circumstances, constitute a disposition subject to the penalty rules. “When an asset is held by an individual in common with another person or persons via joint tenancy, tenancy in common, joint ownership, or a similar arrangement, the asset (or affected portion of the asset) is considered to be transferred by the individual when any action is taken, either by the individual or any other person, that reduces or eliminates the individual’s ownership or control of the asset.” HCFA 64, § 3258.7. Depending on the nature of joint ownership, control may be as significant as ownership. For example, adding a joint owner to a checking is not a disposition subject to a penalty because each owner has the right to withdraw funds. If the joint owner actually withdraws funds, then a disposition subject to the rule has occurred because the applicant no longer has access to the funds. Adding a joint owner to an asset might be subject to the transfer penalty rules if that action limits the applicant’s right to sell or dispose of the asset. HCFA 64, § 3258.7.

Transfers to a trust are treated separately under section 1396p(d). A transfer to an irrevocable trust is subject to the penalty rules if there is no circumstance under which the settlor could receive income and/or principal. Transfers are disregarded (under the penalty provisions) to the full extent the settlor could receive income and/or principal under any circumstances. Transfers to a revocable trust are disregarded to the full extent the settlor could recover the trust assets. If payments are made from the trust to someone other than the settlor, the disbursements are subject to the penalty rules.

As noted, some dispositions are not subject to the penalty, either because FMV was received or because an exception to the rule applies. Section 2342 of the Georgia ABD Manual provides that the following dispositions are not subject to the penalty:

• An asset is used to pay a valid debt.

• An asset is a valid loan.

• An A/R transfers an asset to his/her community spouse, or to another individual for the sole benefit of the spouse. See Section 2502,Chart 2502.1, for a definition of sole benefit of

• An A/R can provide a satisfactory showing that he/she intended to dispose of the asset for fair market value, or for other valuable considerations. This would include situations where an individual is defrauded or executes a transfer as a result of misrepresentation.

• All of the transferred resources/assets have been returned to the individual.

• Denial of eligibility would cause an undue hardship. Undue hardship must be considered in every case. Refer to Section 2345, Undue Hardship.

• An asset was transferred exclusively for a purpose other than to qualify for Medicaid. NOTE: This policy does not apply to transfer of homeplace property.

• An asset owned by the community spouse of an institutionalized A/R is transferred by the community spouse after eligibility is established. EXCEPTION: annuities and homeplace property.

• An asset was transferred to a blind or disabled child (minor or adult) as established under title XVI or defined in section 1614 of the Social Security Act.

• The homeplace was transferred (1) to the community spouse of the A/R or (2) child of the A/R if the child is under the age of 21 or is blind or is permanently and totally disabled.

• The homeplace was transferred to a sibling of a LA-D A/R if the sibling has an equity interest in the home and has been residing in the home for at least one year immediately prior to the A/R entering LA-D.

• The homeplace was transferred to a son or daughter of the A/R who has been residing in the home for at least two years immediately prior to the A/R entering LA-D, and the son or daughter was providing such care to the A/R as to permit the A/R to continue to reside at home rather than enter LA-D.

• The assets were transferred to a trust established for the sole benefit of (1) the A/R’s disabled child or (2) a disabled individual who is under 65 years of age. Use the same definition of sole benefit of as for transfer to a spouse. See Section 2502, Chart 2502.1.

• The transferred asset was any resource other than a homeplace that can be excluded under FBR policy.

• The resource was excluded under Non-FBR policy and was transferred into a trust.

The effective date of a transfer or disposition is the first moment of the month following a valid transfer. See POMS § SI 01150.001(B)(2).

Many people misunderstand the rule and believe all dispositions are prohibited. That is why we break the elements apart and why subsection (c)(1) must be read as a whole. Only those dispositions for “less than fair market value” are potentially subject to a penalty.

3. Assets

The term “assets is defined at 42 U.S.C. § 1396p(h)(1) as follows: “with respect to an individual, includes all income and resources of the individual and of the individual’s spouse, including any income or resources which the individual or such individual’s spouse is entitled to….”

The term “resources” has the meaning given to it in section 1382b of this title, without regard (in the case of an institutionalized individual) to the exclusion described in subsection (a)(1) of such section.

HCFA 64, § 3257(4) provides:

the definition of resources is the same definition used by the Supplemental Security Income (SSI) program, except that the home is not excluded for institutionalized individuals. In determining whether a transfer of assets or a trust involves an SSI-countable resource, use those resource exclusions and disregards used by the SSI program, except for the exclusion of the home for institutionalized individuals.

…

However, in determining whether and how a trust is counted in determining eligibility, you may apply more liberal methodologies for resources which you may be using under §1902(r)(2) of the Act. For trust purposes, if you are a 209(b) State, you may use more restrictive definitions of resources that you may have in your State plan.

For noninstitutionalized individuals, the home remains an exempt resource.

4. Less than fair market value

The phrase “fair market value” is not defined in Section 1396p. Section 2342-1 of the Georgia Medicaid Manual defines fair market value (FMV) as an estimate of the value of an asset, if sold at the prevailing price at the time it was actually transferred. Value is based on criteria you use in appraising the value of assets for the purpose of determining Medicaid eligibility. For an asset to be considered transferred for FMV, the compensation received for the asset must be in a tangible form with intrinsic value. If the individual received FMV for the transferred resource, the issue of the transfer is closed and the period of ineligibility does not apply. See POMS SI 01150.005(E).

The phrase “less than fair market value” includes transactions that are penalized in-part because full value is not received. “Compensation” is the cash or other valuable consideration received in exchange for the resource. Uncompensated value is “the difference between the FMV of the asset at the time of the transfer and compensation received for the resource.” See Georgia ABD Manual § 2342-2.

Example: Your home is worth $100,000. You sell it to your son for $50,000. Therefore, if this transaction occurred during the look-back period, a penalty will be assessed on $50,000 of uncompensated value.

Other valuable consideration should include necessary transaction costs, so long as the rate is reasonable and customary.

Example: You list your home with a realtor for $100,000. Sam purchases the home for $100,000, but Jill, the realtor, is paid a 6% commission. If the commission Jill charged is the reasonable and customary rate, then you received $94,000 from Sam, plus $6,000 in services from Jill. Thus, there is no uncompensated value.

Although services purchased in the market place, in most circumstances, have value, services provided by a family member presumptively have no intrinsic value. Instead, Medicaid presumes those services are provided for free. HCFA 64 addresses this issue in a note found at Section 3258.1(A)(1):

while relatives and family members legitimately can be paid for care they provide to the individual, HCFA presumes that services provided for free at the time were intended to be provided without compensation. Thus, a transfer to a relative for care provided for free in the past is a transfer of assets for less than fair market value. However, an individual can rebut this presumption with tangible evidence that is acceptable to the State. For example, you may require that a payback arrangement had been agreed to in writing at the time services were provided.

Selling property for less than the asking price is not necessarily a sale for less than current market value. POMS SI 01150.005(c)(4) states “When the individual attempts to sell a resource on the open market, generally he or she offers it at a particular price. When the sale is made, the individual may accept compensation that is lower than the original asking price. If the property was sold on the open market, this difference between the asking price and the sale price is not uncompensated value. The price paid on the open market establishes the CMV for that item.”

Converting a countable asset into an exempt asset is not a transfer for less than fair market value. In Lopes v. Dep’t of Soc. Servs., 696 F.3d 180 (2nd Cir. 2011), the court noted that 20 C.F.R. § 416.1207(c) contemplates than an individual may trade resources that count against eligibility for those which are exempt. “The Medicaid program categorically excludes certain assets, such as a home and one automobile, from consideration as resources. 42 U.S.C. §§ 1396r-5(c)(5) & 1382b(a). How recently those assets were purchased does not appear to matter in determining whether they should be excluded from the relevant pool of resources. Accordingly, that Lopes converted cash to an annuity shortly before applying for Medicaid is irrelevant to whether the annuity, in its current form, qualifies as a resource under the applicable SSI regulations.”

The POMS indicate that spending cash is presumed to be acceptable. “Assume, absent evidence to the contrary, that an individual gets fair market value when he/she spends cash resources.” See POMS § SI 01150.001(B)(4). Thus, in most cases it is unnecessary to justify every living expense incurred during the look-back period.

The POMS recognize that some resources do not have value so giving them away does not make them subject to the transfer penalty rules. POMS SI 01150.005(c)(4) provides:

If an individual gave away a resource because he or she was unable to sell it at the estimated CMV, it may indicate that the asking price was too high, but the resource still has a value. However, in rare cases the resource may have no value. Although it would still be considered a resource even if it has no value, transferring a resource with no value does not result in any uncompensated value. To develop the issue of resources with no value, see SI 01140.044. If the individual still owns the resource and alleges not being able to sell it, inform the individual about conditional benefits. For conditional benefits, see SI 01150.200.

5. Look-back

The look-back is the period of time Medicaid analyzes transactions to determine whether a penalty should be applied. Prior to February 8, 2006, the look-back was 36 months for transfers to individuals and 60 months for transfers to trusts. Since February 8, 2006, the look-back period is 60 months for all transfers for less than fair market value. 42 U.S.C. § 1396p(c)(1)(B)(i). If a transaction is older than the look-back period, then Medicaid ignores it.

Example: Fifty-nine months ago you transferred $100,000 to your daughter as a gift. You apply for Medicaid. The gift was made within the last 60 months, so it is within the look-back period and is subject to a transfer penalty.

Example: Sixty-one months ago you transferred $100,000 to your daughter as a gift. You apply for Medicaid. The gift was not made within the last 60 months, so it is not within the look-back period and will not be subject to a transfer penalty.

Although the length of the look-back has changed since HCFA 64 was published, section 3258.4 addresses this issue as follows:

The look-back date is the earliest date on which a penalty for transferring assets for less than fair market value can be assessed. Penalties can be assessed for transfers which take place on or after the look-back date. Penalties cannot be assessed for transfers which take place prior to the look-back date. The look-back date varies for individuals transferring assets, depending on whether they are institutionalized, and there are special rules for some trusts, as described in subsection E. (Emphasis added).

6. Look-back date

The look-back date is the point to which Medicaid looks back. Thus, term describes the earliest point in time when a transfer may be penalized under the rule. The point from which Medicaid looks-back is called the “baseline date.” Subsection (c)(1)(B)(ii) describes the baseline date and provides:

With respect to—

(I) an institutionalized individual is the first date as of which the individual both is an institutionalized individual and has applied for medical assistance under the State plan, or

(II) a noninstitutionalized individual is the date on which the individual applies for medical assistance under the State plan or, if later, the date on which the individual disposes of assets for less than fair market value.

Of note, subsection (c)(1) states that transactions “on or after” the baseline date are also subject to the rule. Thus, the following examples apply:

Example: You are admitted to a nursing home on March 1, 2021 and apply for Medicaid. The ending date is March, 2021 and Medicaid looks-back 60 months to analyze all transfers for less than fair market value since April 30, 2016.

Example: You are admitted to the nursing home on March 1, 2021. On March 5, 2021, you give away your home. The transaction occurred after the look-back date so it is subject to the penalty provisions.

7. Penalty beginning date

For transfers prior to February 8, 2006, the penalty begins to run on the date the assets were transferred unless the transfer occurred within a period of ineligibility. 42 U.S.C. § 1396p(c)(1)(D)(i). “The penalty date is the beginning date of each penalty period that is imposed for an uncompensated transfer. The penalty date for all individuals who transfer assets for less than fair market value is the first day of the month in which the asset was transferred (or, at State option, the first day of the month following the month of transfer), provided that date does not occur during an existing penalty period.” HCFA 64, § 3258.5(A).

For transfers on and after February 8, 2006, the penalty begins on the later of the first day of the month after the date assets were transferred, or when the individual would otherwise be receiving institutional level care described in subparagraph (C) based on an approved application for such care but for the application of the penalty period. 42 U.S.C. § 1396p(c)(1)(D)(ii).

8. The penalty period and its length

The penalty period is the period of time during which payment for specified services is denied. HCFA 64, § 3258.5(B). The issue of value is critical to a determination of the length of the penalty because the larger the value, the longer the penalty. There is no limit on the length of a penalty. The penalty length “is based solely on the value of the assets transferred and the cost of nursing facility care.” HCFA 64, § 3258.5(B).

Institutionalized individuals. (i)With respect to an institutionalized individual, the number of months of ineligibility under this subparagraph for an individual shall be equal to—

(I) the total, cumulative uncompensated value of all assets transferred by the individual (or individual’s spouse) on or after the look-back date specified in subparagraph (B)(i), divided by

(II) the average monthly cost to a private patient of nursing facility services in the State (or, at the option of the State, in the community in which the individual is institutionalized) at the time of application.

Example:

Gift amount $100,000

Divisor – $9,584 (from 4/1/23)

Penalty period = 10.43

Non-institutionalized individuals. (ii)With respect to a noninstitutionalized individual, the number of months of ineligibility under this subparagraph for an individual shall not be greater than a number equal to—

(I) the total, cumulative uncompensated value of all assets transferred by the individual (or individual’s spouse) on or after the look-back date specified in subparagraph (B)(i), divided by

(II) the average monthly cost to a private patient of nursing facility services in the State (or, at the option of the State, in the community in which the individual is institutionalized) at the time of application.

Example:

Gift amount $100,000

Divisor – $9,584 (from 4/1/23))

Penalty period = 10.43

If the institutionalized individual was penalized as a non-institutionalized person, or vice versa, then the penalty for one is reduced by the number of months the individual was penalized under the other. Subsection (c)(1)(E)(iii).

States are now prohibited from rounding down any penalty. Subsection (c)(1)(E)(iv).

After a penalty period begins, it runs until it is complete and is not tolled. See New Medicaid Transfer of Asset Rules Under the Deficit Reduction Act of 2005, Section II(A), attached to SMDL# 06-018 (July 27, 2006). This was addressed in HCFA 64, § 3258.5(K).

9. Excluded services

For Institutionalized individuals, the services which are not covered during a penalty are those in subsection (c)(i).

(i) The services described in this subparagraph with respect to an institutionalized individual are the following:

(I) Nursing facility services.

(II) A level of care in any institution equivalent to that of nursing facility services.

(III) Home or community-based services furnished under a waiver granted under subsection (c) or (d) of section 1396n of this title.

For noninstitutionalized individuals, the services which are not covered during a penalty are those in (c)(ii).

(ii) The services described in this subparagraph with respect to a noninstitutionalized individual are services (not including any services described in clause (i)) that are described in paragraph (7), (22), or (24) of section 1396d(a) of this title, and, at the option of a State, other long-term care services for which medical assistance is otherwise available under the State plan to individuals requiring long-term care.

Services other than excluded services should still be available (e.g., payment for prescription drugs). See HCFA 64, § 3258.5 and § 3258.8.

10. Procedure

Imposition of a penalty requires a denial notice. If a penalty period is imposed on an individual who is already eligible for Medicaid, the State must provide a 10-day adverse action notice. As well as complying with existing legal requirements (see regulations at 42 CFR 431 Subpart E), this notice must contain information about the undue hardship exception. See New Medicaid Transfer of Asset Rules Under the Deficit Reduction Act of 2005, Section II(A), attached to SMDL# 06-018 (July 27, 2006).

11. Special Rule: Annuities

Subsections (F) and (G) were added as part of the Deficit Reduction Act of 2005 (“DRA”) and relate to annuities.

Subsection (F) provides:

For purposes of this paragraph, the purchase of an annuity shall be treated as the disposal of an asset for less than fair market value unless—

(i) the State is named as the remainder beneficiary in the first position for at least the total amount of medical assistance paid on behalf of the institutionalized individual under this subchapter; or

(ii) the State is named as such a beneficiary in the second position after the community spouse or minor or disabled child and is named in the first position if such spouse or a representative of such child disposes of any such remainder for less than fair market value.

Subsection (G) provides:

For purposes of this paragraph with respect to a transfer of assets, the term “assets” includes an annuity purchased by or on behalf of an annuitant who has applied for medical assistance with respect to nursing facility services or other long-term care services under this subchapter unless—

(i) the annuity is—

(I) an annuity described in subsection (b) or (q) of section 408 of the Internal Revenue Code of 1986; or

(II) purchased with proceeds from—

(aa) an account or trust described in subsection (a), (c), or (p) of section 408 of such Code;

(bb) a simplified employee pension (within the meaning of section 408(k) of such Code); or

(cc) a Roth IRA described in section 408A of such Code; or

(ii) the annuity—

(I) is irrevocable and nonassignable;

(II) is actuarially sound (as determined in accordance with actuarial publications of the Office of the Chief Actuary of the Social Security Administration); and

(III) provides for payments in equal amounts during the term of the annuity, with no deferral and no balloon payments made.

In Georgia, subsections (F) and (G) are not applied in the alternative. In Cook v. Glover, 295 Ga. 495 (2014), the Georgia Supreme Court held that 42 U.S.C. § 1396p(c)(1) is ambiguous concerning whether compliance with both subsections (F) and (G) is required, or whether they apply in the alternative. Applying a Chevron-type analysis, the Court adopted the agency’s interpretation regarding how these subsections should be applied. Thus, compliance with both provisions is required.

Even if an annuity is determined to meet the requirements above, and the purchase is not treated as a transfer, if the annuity or the income stream from the annuity is transferred, except to a spouse or to another individual for the sole benefit of the spouse, child or trust as described in 1917(c)(2)(B), that transfer may be subject to penalty.

12. Special Rule: Fractional gifts

Prior to DRA, States had the option to disregard gifts for less than the penalty divisor and round down fractional amounts. Thus, it was possible to engage in a pattern of monthly gifting without the imposition of a transfer of resources penalty. Subsection (H) was added to Section 1396p(c)(1) to reverse that result. Now, multiple fractional gifts are totaled, and a penalty is imposed on the cumulative transfer. Subsection (H) provides as follows:

Notwithstanding the preceding provisions of this paragraph, in the case of an individual (or individual’s spouse) who makes multiple fractional transfers of assets in more than 1 month for less than fair market value on or after the applicable look-back date specified in subparagraph (B), a State may determine the period of ineligibility applicable to such individual under this paragraph by—

(i) treating the total, cumulative uncompensated value of all assets transferred by the individual (or individual’s spouse) during all months on or after the look-back date specified in subparagraph (B) as 1 transfer for purposes of clause (i) or (ii) (as the case may be) of subparagraph (E); and

(ii) beginning such period on the earliest date which would apply under subparagraph (D) to any of such transfers.

13. Special Rule: Promissory notes

DRA included provisions relating to promissory notes. The DRA rules were intended to eliminate perceived abuse which is described as follows:

Some States have experienced problems with individuals who have attempted to circumvent rules penalizing transfers of assets by obtaining promissory notes, loans, or mortgages containing a promise of repayment from transferees. Individuals would then present the note, loan or mortgage instruments at the time of their Medicaid application for long-term care services in order to establish that these transactions were actually loans, not gifts. In some cases, these were merely sham transactions, and repayment of the full amount transferred was neither expected nor enforced. Various techniques, such as balloon payments, in which token payments are made for most of the term of the loan with the balance due in a lump sum at the very end of the loan, and cancellation of the loan upon the death of the transferor, were used to ensure that the transferee would in fact retain most, if not all, of the funds.

Subsection (I) now provides that funds used to purchase a promissory note, loan or mortgage are “assets” with respect to a transfer of assets unless the note, loan or mortgage

(i) has a repayment term that is actuarially sound (as determined in accordance with actuarial publications of the Office of the Chief Actuary of the Social Security Administration);

(ii) provides for payments to be made in equal amounts during the term of the loan, with no deferral and no balloon payments made; and

(iii) prohibits the cancellation of the balance upon the death of the lender.

If the above criteria are not met, then the purchase of the promissory note, loan or mortgage is treated as a transfer of assets. You can use a worksheet located here to estimate the penalty period when a promissory note is used in conjunction with a gift.

14. Special Rule: Life estates

DRA added subsection (J) which provides with respect to a transfer of assets, the term “assets” includes the purchase of a life estate interest in another individual’s home unless the purchaser resides in the home for a period of at least 1 year after the date of the purchase.

This provision was added to curb perceived abuse which is explained as follows:

Another technique used by individuals in some States to avoid transfer of assets penalties was the purchase of a life estate interest in another individual’s home. The individual purchasing the life interest in the home would allege that something of value, i.e., the life estate, had been received in exchange for the funds paid. However, in many cases, the purchaser never lived in the home nor derived any benefit from the life estate, and was in effect making a gift to the owner, who still retained the remainder interest. Since some States have elected to use more liberal resource methodologies and do not count life estate interests as resources, the value of the life estate was excluded in determining Medicaid eligibility. Thus, the acquisition of a life estate in the property of another would serve to transform countable resources (cash) into a non-countable resource (the life estate).

The DRA provisions in (J) do not apply to the retention or reservation of life estates by individuals transferring real property. “In such cases, the value of the remainder interest, not the life estate, would be used in determining whether a transfer of assets has occurred and in calculating the period of ineligibility.”

15. Exemptions: Transfers of the home

42 U.S.C. § 1396p(c)(2)(A) provides:

An individual shall not be ineligible for medical assistance by reason of paragraph (1) to the extent that—

(A) the assets transferred were a home and title to the home was transferred to—

(i) the spouse of such individual;

(ii) a child of such individual who

(I) is under age 21, or

(II) (with respect to States eligible to participate in the State program established under subchapter XVI of this chapter) is blind or permanently and totally disabled, or (with respect to States which are not eligible to participate in such program) is blind or disabled as defined in section 1382c of this title;

(iii) a sibling of such individual who has an equity interest in such home and who was residing in such individual’s home for a period of at least one year immediately before the date the individual becomes an institutionalized individual; or

(iv) a son or daughter of such individual (other than a child described in clause (ii)) who was residing in such individual’s home for a period of at least two years immediately before the date the individual becomes an institutionalized individual, and who (as determined by the State) provided care to such individual which permitted such individual to reside at home rather than in such an institution or facility.

16. Exemptions: Other transfers

42 U.S.C. § 1396p(c)(2)(B) provides:

An individual shall not be ineligible for medical assistance by reason of paragraph (1) to the extent that— the assets

(i) were transferred to the individual’s spouse or to another for the sole benefit of the individual’s spouse,

(ii) were transferred from the individual’s spouse to another for the sole benefit of the individual’s spouse,

(iii) were transferred to, or to a trust (including a trust described in subsection (d)(4) of this section) established solely for the benefit of, the individual’s child described in subparagraph (A)(ii)(II), or

(iv) were transferred to a trust (including a trust described in subsection (d)(4) of this section) established solely for the benefit of an individual under 65 years of age who is disabled (as defined in section 1382c(a)(3) of this title.

The exception in (c)(2)(B)(i) is unlimited. See HCFA 64, § 3258.11.

At times, the comma in subsection (iii) is overlooked. There is no requirement that assets be transferred to a trust for a disabled child; they may be transferred directly to that child. The issue with such transfers is whether the transfer creates an eligibility issue for a child who is receiving means-tested benefits.

If assets are transferred to a disabled person other than a child, that person must be under 65 and they must go in trust to satisfy the terms of the exemption. Thus, a transfer to a disabled grandchild would be to a trust for his or her sole benefit.

In Hobbs. v. Zenderman, 579 F.3d 1171 (10th Cir. 2009), the applicant argued that eligibility was denied in violation of 1396p(c)(2)(B)(iii). The Court found it was not the transfer to the trust which cause ineligibility. Hobbs was denied eligibility because the Trust was not being administered for Hobbs’ sole benefit and was thus a countable resource.

The sole benefit rule is discussed as follows in HCFA 64 at section 3257(b)(6):

A transfer is considered to be for the sole benefit of a spouse, blind or disabled child, or a disabled individual if the transfer is arranged in such a way that no individual or entity except the spouse, blind or disabled child, or disabled individual can benefit from the assets transferred in any way, whether at the time of the transfer or at any time in the future.

Similarly, a trust is considered to be established for the sole benefit of a spouse, blind or disabled child, or disabled individual if the trust benefits no one but that individual, whether at the time the trust is established or any time in the future. However, the trust may provide for reasonable compensation, as defined by the State, for a trustee or trustees to manage the trust, as well as for reasonable costs associated with investing or otherwise managing the funds or property in the trust. In defining what is reasonable compensation, consider the amount of time and effort involved in managing a trust of the size involved, as well as the prevailing rate of compensation, if any, for managing a trust of similar size and complexity.

A transfer, transfer instrument, or trust that provides for funds or property to pass to a beneficiary who is not the spouse, blind or disabled child, or disabled individual is not considered to be established for the sole benefit of one of these individuals. In order for a transfer or trust to be considered to be for the sole benefit of one of these individuals, the instrument or document must provide for the spending of the funds involved for the benefit of the individual on a basis that is actuarially sound based on the life expectancy of the individual involved. When the instrument or document does not so provide, any potential exemption from penalty or consideration for eligibility purposes is void.

An exception to this requirement exists for trusts discussed in §3259.7. Under these exceptions, the trust instrument must provide that any funds remaining in the trust upon the death of the individual must go to the State, up to the amount of Medicaid benefits paid on the individual’s behalf. When these exceptions require that the trust be for the sole benefit of an individual, the restriction discussed in the previous paragraph does not apply when the trust instrument designates the State as the recipient of funds from the trust. Also, the trust may provide for disbursal of funds to other beneficiaries, provided the trust does not permit such disbursals until the State’s claim is satisfied. Finally, “pooled” trusts may provide that the trust can retain a certain percentage of the funds in the trust account upon the death of the beneficiary.

When a transfer to a disabled individual is alleged, Medicaid must verify the disability of the transferee unless it can confirm the transferee is receiving SSI and/or Medicaid. HCFA 64, § 3258.10(B)(2). Section 3258.10(B) also provides: “In determining whether an asset was transferred for the sole benefit of a spouse, child, or disabled individual, ensure that the transfer was accomplished via a written instrument of transfer (e.g., a trust document) which legally binds the parties to a specified course of action and which clearly sets out the conditions under which the transfer was made, as well as who can benefit from the transfer. A transfer without such a document cannot be said to have been made for the sole benefit of the spouse, child, or disabled individual, since there is no way to establish, without a document, that only the specified individuals will benefit from the transfer.”

See also Streimer Letter, and see H. Krooks, The Sole Benefit Trust.

17. Exemptions: Intent to dispose of assets for FMV

42 U.S.C. § 1396p(c)(2)(C)(i) provides:

An individual shall not be ineligible for medical assistance by reason of paragraph (1) to the extent that— a satisfactory showing is made to the State (in accordance with regulations promulgated by the Secretary) that

the individual intended to dispose of the assets either at fair market value, or for other valuable consideration.

POMS SI 01150.005(c)(4) addresses situations where an individual intended to get fair market value.

a. Resource sold

When the individual attempts to sell a resource on the open market, generally he or she offers it at a particular price. When the sale is made, the individual may accept compensation that is lower than the original asking price. If the property was sold on the open market, this difference between the asking price and the sale price is not uncompensated value. The price paid on the open market establishes the CMV for that item. If the property was sold on the open market, assume that the individual received FMV. However, if the property was not sold on the open market (e.g., it was sold to a relative) see SI 01150.005D.6. in this section.

b. Resource is not sold

If an individual gave away a resource because he or she was unable to sell it at the estimated CMV, it may indicate that the asking price was too high, but the resource still has a value. However, in rare cases the resource may have no value. Although it would still be considered a resource even if it has no value, transferring a resource with no value does not result in any uncompensated value. To develop the issue of resources with no value, see SI 01140.044. If the individual still owns the resource and alleges not being able to sell it, inform the individual about conditional benefits. For conditional benefits, see SI 01150.200.

HCFA 64, § 3258.10(C)(1) provides:

In determining whether an individual intended to dispose of an asset for fair market value or for other valuable consideration you should require that the individual establish, to your satisfaction, the circumstances which caused him or her to transfer the asset for less than fair market value. Verbal statements alone generally are not sufficient. Instead, require the individual to provide written evidence of attempts to dispose of the asset for fair market value, as well as evidence to support the value (if any) at which the asset was disposed.

18. Exemptions: Exclusively for a purpose other than Medicaid

42 U.S.C. § 1396p(c)(2)(C)(i) provides:

An individual shall not be ineligible for medical assistance by reason of paragraph (1) to the extent that— a satisfactory showing is made to the State (in accordance with regulations promulgated by the Secretary) that

the assets were transferred exclusively for a purpose other than to qualify for medical assistance.

POMS SI 01150.125 addresses transfers other than for qualification purposes. There is a rebuttable presumption that gifted resources were given away to establish or maintain eligibility. The presumption can be rebutted, but only if convincing evidence is provided showing the transfer was exclusively for a purpose other than becoming or remaining eligible for benefits. See POMS SI 01150.125(B).

POMS SI 01150.125(C) provides the following examples of convincing evidence:

- Documents showing that the transfer was not within the individual’s control (e.g., was ordered by a court); or

- Documents establishing that, at the time of the transfer, the individual could not have anticipated SSI eligibility (e.g., the individual became disabled following a traumatic accident, but was not disabled at the time the transfer occurred); or

- Documents which verify the unexpected loss of other resources or income which would have precluded SSI eligibility (e.g., a divorce which results in loss of income or resources provided by a spouse); or

- Documents establishing that, at the time of the transfer, the transferred resource would have been an excluded resource under SSI rules (e.g., documents that establish the type of resource, the value, the date of transfer, etc.).

POMS SI 01150.125(D) provides the following examples of a purpose other than to obtain benefits:

- After the transfer there is a traumatic onset (e.g., traffic accident) of disability or blindness that leads to SSI eligibility;

- After the transfer, there is a diagnosis of a previously undetected disabling condition that leads to SSI eligibility;

- After the transfer, there is an unexpected loss of other income or resources (including deemed) which would have precluded SSI eligibility;

- In the month of the transfer, the transferred resource would have been excludable for SSI purposes (SI 01130.050);

- In the month of transfer, total countable resources would have been below the $2,000 resource limit ($3,000 for a couple) even if the individual had retained the transferred resource;

- The transfer was court-ordered (provided the individual took no action to petition the court to order the transfer);

- The resources were given to a religious order by a member of that order in accordance with a vow of poverty.

HCFA 64, § 3258.10(C)(2) provides:

Require the individual to establish, to your satisfaction, that the asset was transferred for a purpose other than to qualify for Medicaid. Verbal assurances that the individual was not considering Medicaid when the asset was disposed of are not sufficient. Rather, convincing evidence must be presented as to the specific purpose for which the asset was transferred.

In some instances, the individual may argue that the asset was not transferred to obtain Medicaid because the individual is already eligible for Medicaid. This may, in fact, be a valid argument. However, the validity of the argument must be determined on a case-by-case basis, based on the individual’s specific circumstances. For example, while the individual may now be eligible for Medicaid, the asset in question (e.g., a home) might be counted as a resource in the future, thus compromising the individual’s future eligibility. In such a situation, the argument that the individual was already eligible for Medicaid does not suffice.

19. Exemptions: Curing the penalty

42 U.S.C. § 1396p(c)(2)(C)(i) provides:

An individual shall not be ineligible for medical assistance by reason of paragraph (1) to the extent that— a satisfactory showing is made to the State (in accordance with regulations promulgated by the Secretary) that

all assets transferred for less than fair market value have been returned to the individual.

HCFA 6, § 3258.10(C)(3) provides:

When all assets transferred are returned to the individual, no penalty for transferring assets can be assessed. In this situation, you must ensure that any benefits due on behalf of the individual are, in fact, paid. When a penalty has been assessed and payment for services denied, a return of the assets requires a retroactive adjustment, including erasure of the penalty, back to the beginning of the penalty period.

However, such an adjustment does not necessarily mean that benefits must be paid on behalf of the individual. Return of the assets in question to the individual leaves the individual with assets which must be counted in determining eligibility during the retroactive period. Counting those assets as available may result in the individual being ineligible for Medicaid for some or all of the retroactive period, (because of excess income/resources) as well as for a period of time after the assets are returned.

It is important to note that, to void imposition of a penalty, all of the assets in question or their fair market equivalent must be returned. If, for example, the asset was sold by the individual who received it, the full market value of the asset must be returned to the transferor, either in cash or another form acceptable to the State.

When only part of an asset or its equivalent value is returned, a penalty period can be modified but not eliminated. For example, if only half the value of the asset is returned, the penalty period can be reduced by one-half.