“Long-term care covers a diverse array of services provided over a sustained period of time to people of all ages with chronic conditions and functional limitations. Their needs for care range from minimal personal assistance with basic activities of everyday life (ADLs) to virtually total care.” Institute of Medicine, Improving the Quality of Long-Term Care, p.36 (National Academy Press 2001). Long-term care is typically how we help those with functional deficits cope between acute care situations (i.e. doctor visits). It is a day-in-day-out process.

Long-term care is designed to meet a person’s health or personal care needs during a short or long period of time. LTC services help people live as independently and safely as possible when they can no longer perform everyday activities on their own. Long-term care is provided in different places by different caregivers, depending on a person’s needs. Most long-term care is provided at home by unpaid family members and friends. It can also be given in a facility such as a nursing home or in the community, for example, in an adult day care center.

It is difficult to predict how much or what type of long-term care a person might need. Several things increase the risk of needing long-term care.

- Age. The risk generally increases as people get older.

- Gender. Women are at higher risk than men, primarily because they often live longer.

- Marital status. Single people are more likely than married people to need care from a paid provider.

- Lifestyle. Poor diet and exercise habits can increase a person’s risk.

- Health and family history. These factors also affect risk.

Unfortunately, health care often fails to meet the needs of chronically ill people. Treatment regimens for chronic illness often do not conform to evidence-based guidelines. Care may be rushed and overly dependent on patient-initiated follow-up. In part, recognition of these problems resulted in development of the Chronic Care Model at the Improving Chronic Illness Care program at the MacColl Center for Health Care Innovation. That model identified the “informed, activate patient” (or surrogate) as an essential element of the chronic care team.

Here are several thoughts concerning what good long-term care should look like. First, good care should be planned. Each patient should have a medical home. Each patient should adopt his or her own set of goals concerning quality of life and that this should be done in a context separate from the treating health care provider to eliminate any appearance of conflict. Good planning should begin early and should incorporate the patient’s values.

Second, long-term care should be accessible. If a patient cannot access care, then needs remain unmet. Unmet needs will result in danger zones where the need for additional care and loss of function can accelerate.

Third, long-term care should be proactive. Do not wait until an injury occurs to develop a plan for providing care. Whether a particular plan is put into effect may be a function of patient choice, but care should be forward-looking and designed to minimize the likelihood that someone who is aging in place declines unnecessarily.

Fourth, long-term care should be systematic. This is not to say that individuality is ignored; it simply recognizes that many tasks associated with long-term care are routine and a system should be in place to ensure that care is provided as needed.

Fifth, care should be individualized. While the medical literature indicates that as we age, we become more different. We remain a society of “doer’s” rather than “listeners.” We focus on task efficiency, forgetting that we are dealing with people. Good care is not simply the absence of bad outcomes; it is the enhancement of quality of life.

Sixth and closely related to the fifth, care should involve the patient and should answer questions. Good care is interactive, invoking the informed consent process. Good communication and comprehensibility are essential to the process of involving the patient.

Seventh, care should be comprehensive, at least in the sense that it is holistic and meets the patient’s needs and desires. It should account for a person’s physical, mental and psycho-social well-being.

Eighth, good care should be measurable. There should be standards for determining whether care is meeting the needs of the individual and appropriate care should be provided at each instance when it is needed.

Ninth, long-term care should be consistent. Although consistency is related to measurability and systematic delivery, we believe this concept differs enough for separate discussion.

Finally, providers must be accountable to their patients. Accountability comes in many forms such as market choice – if a provider is non-responsive then the patient simply goes elsewhere. Accountability may take different forms such as through litigation. But in this context, we believe accountability means personalized care designed to ensure that outcomes are consistent with planning goals.

Other important principles include: health care should be affordable, cost efficient, and should seek to meet the needs of underserved populations.

Good care invokes not just consideration of what is done, but how, where and for how long it is done. These considerations take into account patient preferences as well as the preferences and abilities of caregivers. Overburdening caregivers results in burnout, which will cause the plan to fail. These considerations necessarily require exploration of what older people want from long-term care. Most elders want to remain home. They want to maintain independence for as long as possible, although the meaning of independence will vary from person to person. Also, most elders want to manage change.

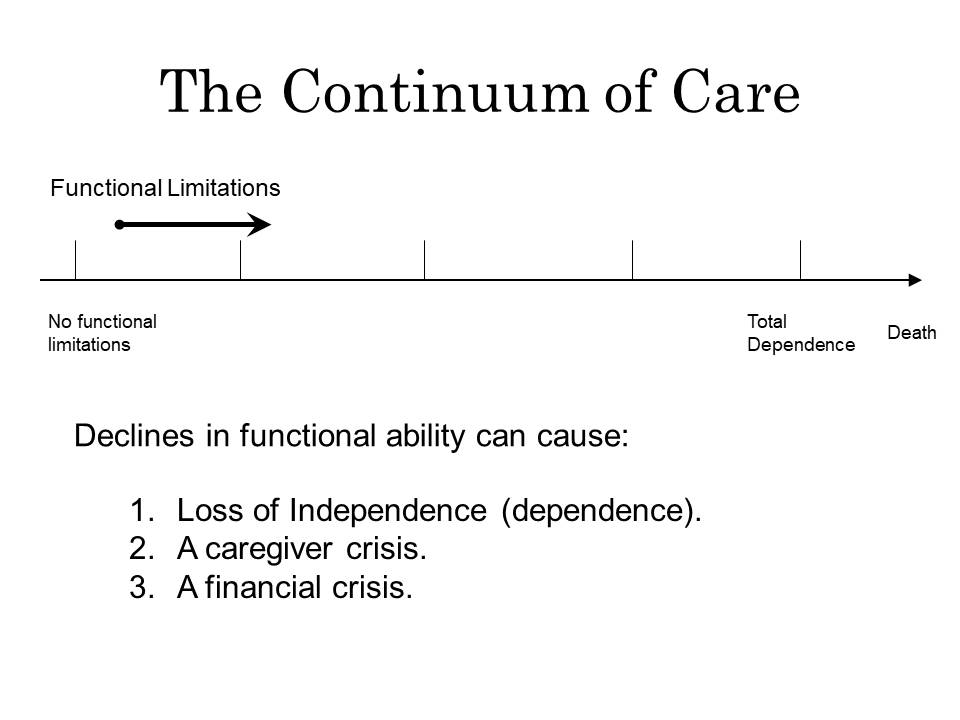

Continuum of Care

Long-term care is provided over time as individuals with chronic illnesses decline in health. Most long-term care is provided at home by family members. When informal care is no longer possible, Elders enter the formal long-term care system. Individuals receiving long-term care tend to tread deeper into the Elder Care Continuum, rarely regaining lost function. On the shallow end the continuum is home, and those with no functional deficits or few care needs tend to be there. In the deepest part of the continuum, the patient needs total care. This tends to be nursing home care. Between these extremes, a panoply of options exists, some of which are described below.

Home

Elders want to stay home. Home can mean anything, but generally speaking, it is where an individual chooses to live. Prior to functional loss, individuals tend to adapt to their environment. After onset of functional loss, the environment often times must adapt to the individual’s needs. When the physical environment can no longer be adjusted to meet the needs of the elder, then additional caregiver resources are required, or a change in environment may be necessary.

Most long-term care is provided at home by family and friends. Isolation, because the Elder is single or after loss of a spouse, can result in a move to a more formal setting. Other conditions leading to a change in housing situation include loss of the caregiver support system, need for assistance with medication management, fear of falling, falls resulting in injury, acute episodes coupled with fear of recurrence or with a decline in condition, wandering, and incontinence. The need for rehabilitation can result in a short-term stay away from home, with the average rehabilitation time being 30 to 40 days.

Home with Family Assistance

Most caregiving is done at home by family members. Most is unpaid. Family assistance can range from giving “mom” a ride to the doctor’s office to providing total care. Unless an elder is being abused, no law requires admission to a formal long-term care institution. However, statistics tell us that because caregiving is hard work, over time caregivers need assistance. Caregiver burnout is not uncommon. Caregivers tend to suffer deleterious mental health effects and from physical problems including increased blood pressure and insulin levels, impaired immune systems and in increase in cardiovascular disease. When the family network breaks down or, preferably before it breaks down, outside assistance should be summoned.

Personal Care Services

Many providers offer home-maker assistance and assistance with non-skilled needs. Services may include self-care assistance such as help with bathing, eating, dressing and toileting or household assistance which includes housekeeping, laundry, meal preparation, shopping and bill paying. Other services such as transportation, sitter/companion and medication monitoring are available. Services are generally available 24 hours a day seven days a week, although round-the-clock care would likely exceed the cost of nursing home care.

Home Health Care

Home health agencies provide skilled nursing and rehabilitative care such as physical, occupational and speech therapy. Often, agencies providing these services will provide ancillary personal services as well. These services are particularly important when the Elder requires regular medical care that is beyond the knowledge and experience of family caregivers.

Adult Day Care

These programs provide social activities, meals, assistance with personal needs, health education and supervision in a safe environment on a temporary basis. Most centers are open Monday through Friday during normal business hours and allow full-time caregivers an opportunity to continue their daily work and family routines while providing supervision and care for the elderly person.

Respite Care

Respite care offers relief for home caregivers by allowing overnight accommodations as well as medical and social supervision in a nursing home or an assisted living facility.

Homes for the Aged

These facilities are designed to provide a place where people who are able to care for themselves with little or no help, may receive room, board and limited personal services. Someone who lives in the home must be physically and mentally capable of finding his or her way out of the building in case of an emergency without the assistance of another person. They are neither staffed nor licensed to provide medical care. Depending on amenities, they may range from apartment style living to something that looks more like a country club.

Continuing Care Retirement Communities (CCRCs)

Continuing care retirement communities (CCRCs) offer seniors long-term contracts that guarantee lifelong shelter and access to specified health care services. In return, residents usually pay a lump-sum entrance fee and regular monthly payments. Depending on the contract, the entrance fee may be nonrefundable, refundable on a declining basis over time, partially refundable, or fully refundable. CCRC residents enjoy an independent lifestyle with the knowledge that if they become sick or frail, their needs will continue to be met, usually on-site. These communities provide a continuum of care from independent housing through skilled nursing care.

Assisted Living Residences

Assisted living is a long-term care option for Elders that is frequently built on a social, rather than medical, model. ALFs are for individuals who need some assistance, but do not require the nursing care provided in a nursing home. These facilities are regulated. Although regulations will differ from State to State, in many areas, they are allowed to help administer medications to the resident. Typically, there are no bed-bound residents.

Among those services provided at assisted living facilities are meal preparation, assistance with medication management, housekeeping, and standby assistance with bathing, dressing, and grooming. The routine provided in this setting will frequently contribute to improvement or stabilization of the resident’s condition. Frequently, home health care can provide therapy or other services in the assisted living home to extend a resident’s ability to stay. Residents who live in assisted living are usually required to transfer independently and must be able to exit the building independently during emergencies. Many assisted living facilities today operate under a hospitality model, leading some to compare them to a docked cruise ship. Residents who enter this level of care typically remain there for two to five years.

Typically, resident danger is associated with an improper admission or an untimely discharge. Proper care at this level will include a comprehensive assessment to determine whether an admission is appropriate (e.g., will the resident be safe) and will also establish a functional baseline. The facility should monitor the resident’s condition on a regular basis and if a decline in condition would put the resident in danger, then the resident should be discharged to a higher level of care. Conditions that typically result in the need for a higher level of care are the progression of dementia, or the need for skilled therapy. Counseling is frequently necessary when a resident must be discharged because either the resident or the resident’s family is in denial.

Memory Care Units

More and more assisted living facilities are establishing memory care units. These units operate on the same social model as other ALFs, but have locked units to prevent wandering.

Nursing Homes

The job of a nursing home is to provide 24-hour nursing care to those who are chronically ill or injured, have health care needs as well as personal needs and are unable to function independently. The team of caregivers in a nursing home includes the administrator, a physician who serves as the facility’s medical director, registered nurses, licensed practical nurses, certified nursing assistants, a dietitian, activity coordinator, social worker and housekeeping staff. Nursing homes may provide two levels of care: intermediate care and skilled care. Intermediate care is typically custodial, although it functions at a higher level than any other care setting. Skilled care provides the residents with more extensive services such as physical, occupational, speech or respiratory therapy. Many nursing homes have an Alzheimer’s unit which is typically secured.

One of the primary problems with nursing home care is the stigma attached to them. Many elders still envision them as the county “old folks home” or the “poor house.” Many people have an expectation that those admitted to a nursing home will get worse, or that a nursing home is a place to die. Sometimes these stigmas lead to depression, which in turn impacts recovery. One nursing home administrator indicated that the best way to confront these out-dated notions is by having people visit the nursing home. Many nursing homes have moved toward hotel style amenities and one administrator indicated that within ten years, consumers will expect nursing homes to deliver medical care “hotel-style.”

One nursing home administrator indicated that learning the resident’s story can contribute to better care. It personalizes the resident. For those who come into the nursing home cognizant, the staff can talk to the resident. For residents with dementia or other conditions that prevent dialog, it is important for family members to let the staff know who Mom or Dad were before their condition declined. “Local” nursing homes sometimes have an immediate bond with residents because staff members knew the resident prior to admission.

More data exists concerning the quality of nursing home care than any other level of care. This is because most nursing homes accept Medicare and Medicaid funds and, therefore, are subject to inspection and reporting requirements. According to the IOM Report “[e]vidence indicates that the quality of nursing home care in general has improved over the past decade, even though nursing homes are serving a more seriously ill population.” This appears to be consistent with other data, such as a GAO report from July 2003 titled Nursing Home Quality: Prevalence of Serious Problems, While Declining, Reinforces Importance of Enhanced Oversight. There, the GAO reported that the magnitude of problems uncovered during standard nursing home surveys remains a cause for concern even though OSCAR deficiency data indicates that state surveyors are finding fewer serious quality problems. Most of the serious survey deficiencies seem to be coming from the same underperforming nursing homes.

Hospice Care

Traditionally hospice care is provided at home. It is palliative care, not curative care, for the terminally ill. It addresses not only physical needs and pain management but also psychological, spiritual and emotional needs for residents, family members and friends. Hospice care is provided through an interdisciplinary, medically directed team. This team approach to care for dying persons typically includes a physician, a nurse, a home health aide, a social worker, a chaplain and a volunteer. Hospice requires a doctor’s order with a prognosis of 6 months. For those who qualify, hospice services are paid for by Medicare and the room and board at the nursing home is paid for privately or by Medicaid. The resident liability which is paid monthly to the nursing home is discontinued. Many times the family benefits more from the services than the resident.

Resources

Long Term Care (Administration on Community Living)

BLOG POSTS

Updates to Nursing Home Quality of Care Regulations

From time to time federal regulations covering nursing home quality of care are updated. Thus far, the following updates have been published in May and June of 2024. Updates posted May 10, 2024 42 CFR Part 483 — Requirements for States and Long Term Care Facilities view changes § 483.5 Definitions. view changes § 483.10 […]

Federal Nursing Home Quality of Care Regulations

Nursing homes that accept Medicare or Medicaid are required to comply with quality of care regulations. Although we have blogged elsewhere on specific nursing home resident rights, the current federal regulations are linked below. 42 CFR Part 483 — Requirements for States and Long Term Care Facilities § 483.5 Definitions. § 483.10 Resident rights. § […]

Long-Term Care Partnership Policies

Long-Term Care Partnership Policies One example of good planning is purchasing long-term care insurance. The greatest risk to non-taxable estates (those under $12.9 million) is the cost of long-term care. With long-term care insurance, you can shift that risk to an insurance company. A partnership policy is a special long-term care insurance policy that protects […]

CMS Announces Nursing Home Minimum Staffing Rule

On April 22, 2024, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services announced a new final rule requiring minimum staffing levels in nursing homes. The new rule applies to all nursing homes that receive funds from Medicare or Medicaid. Nursing homes must provide at least 3.48 hours of care per resident per day. This consists of […]

Washington Post Reports Assisted Living Facilities Using Algorithm to Set Staffing Levels

On April 1, 2024, the Washington Post published an article titled “Algorithms guide senior home staffing. Managers say care is suffering.” The article indicates that a system, called Service Alignment, was developed more than two decades ago when assisted living facility (ALF) executives began timing caregivers performing tasks. That data was fed into a computer […]

New Report cites dangers in relying on data regarding quality of care in Assisted Living Facilities

In February 2024, Justice in Aging released a new report based on California’s “performance measure” data from the state’s Medicaid assisted living program. Aging in Justice concluded that the quality of care measures provide no meaningful information. A perfect score tells you nothing about the quality of care residents receive. The report concludes that the […]

Cost of Long-Term Care

For many years, Genworth has produced a Cost of Care Survey tracking the cost of long-term care in America. According to the survey, the projected national monthly median costs will be as follows: Homemaker Services: $5,417 Home Health Aide: $5,625 Adult Day Health Care: $1,847 Assisted Living Facility: $4,917 Nursing Home Semi-Private Room: $8,641 Nursing […]

Assisted Living Facility Not Entitled to Summary Judgment Where Cognitively Impaired Resident Filmed Nude

In Jones v. Life Care Centers of America (Tenn .Ct. Appeals 2023), a cognitively impaired resident was assisted in the shower by staff. While doing so, the employee took a call from her incarcerated boyfriend which showed the resident’s nude body. The assisted living facility moved for summary judgment after alleging the resident showed no […]

Opting Out of Arbitration Agreements

Ideally, health care providers do the right thing. Good Care is provided. There is no negligence. But what if they don’t do the right thing? What if they are negligent? Should you have the right to consider your options regarding how to hold them accountable? Over the past two decades, many long-term care providers, especially […]

Supreme Court Rules Nursing Home Resident Rights Are Enforceable Under Section 1983

Last year we reported that Talevski v. Health and Hospital Corporation of Marion County (HHC) was headed to the Supreme Court. On June 8, 2023, the U.S. Supreme Court issued its opinion, affirming the Seventh Circuit, and held that the Federal Nursing Home Reform Act (FNHRA) is enforceable under 42 U.S.C. § 1983. Justice Jackson […]